As Josh Frydenberg went to sleep on the night of Wednesday 17 Feburary 2021, he could have been forgiven for resting easily. The News Media Bargaining Code – for which his Department of Treasury had been working to implement – had at long last passed through Australia’s House of Representatives, and was on it’s way to the Senate in the coming week where it would also seemingly pass with multi-partisan support.

The Code had been long-fought for by the Morrison Government on behalf of large Australian and international media organisations, with the development of it (in it’s mandatory form) having been a request made by them to the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission back in April 2020. It’s draft form would be released by the ACCC for public comment in August 2020, and after some modifications it’s final form would be introduced to parliament in December 2020.

Google had run a long and public campaign against the code, but a compromise had been found which meant that the Code (or more accurately the threat of it) would result in extremely large sums of money to pass from Google into the bank accounts of large Australian media organisations. The media being happy with the Government’s actions would set up the Government well for an election that looks increasingly likely this year

That very restful entry to sleep for Frydenberg would have been in stark contrast to his wake from it. That day he, along with over 25 million Australian citizens and residents woke to a Facebook with no news. A significant amount of information and accounts had been removed from it, and some actions for which Australians had been accustomed to performing disallowed. Will Easton, Managing Director of Facebook Australia & New Zealand announced these changes on the Facebook Newsroom blog – the sharing and accessing of news on Facebook in Australia was to be no more.

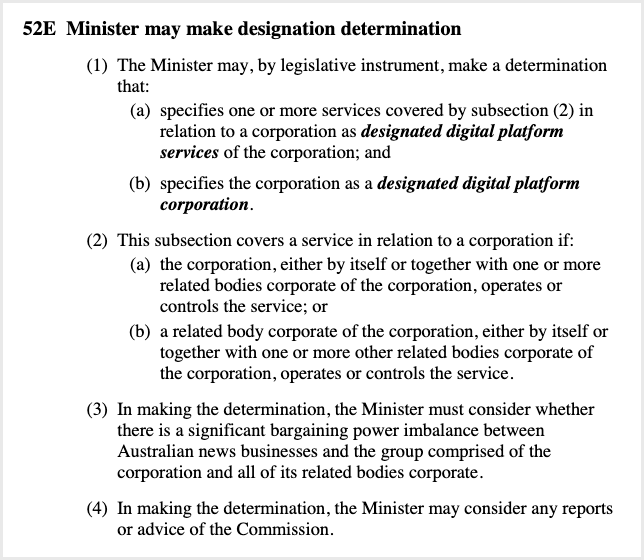

Facebook’s News Feed and Google’s Search product are the two “digital platforms” slated by Frydenberg as ones that will be targeted for “designation” under the Code. The reason for these designations are simple: according to the ACCC, Google and Facebook have a combined share of the digital advertising market of 81 per cent. Note that this 81% number conveniently excludes classifieds and job ads, which is how newspapers used to make a significant amount of their money.

Google and Facebook are simply the only ones with the money worth designating for which there is an interaction with news content. This overnight development threw into question the ability for the Code to achieve it’s aims.

That very restful entry to sleep for Frydenberg would have been in stark contrast to his wake from it. That day he, along with over 25 million Australian citizens and residents woke to a Facebook with no news.

In this article I’m not going to re-litigate the code itself, as I’ve already dissected it in great detail in my submission to the recent Senate inquiry. What I do want to focus on is how an extremely broad and vague definition of what news is under the code has swept up many unwitting publishers and organisations, and made them collateral damage in an international battle between technology and media companies.

The Clever Code

With extremely fortuitous timing, the ABC’s Q&A program was already set to discuss the Code on the very day this pivotal moment occurred. On the panel was Paul Fletcher; the government minister responsible for the Communications portfolio. Minister Fletcher looked quite uncomfortable and perhaps overwhelmed by the direction the conversation was going. He spent most of the show sitting up from his chair and when possible taking the conversation back to previous points in an attempt to overwrite what was said and replace it with the government’s talking points.

The stand-out panellist however was Hal Crawford, founder of Crawford Media Consulting and former Editor-in-chief and Publisher at ninemsn. His description of the code really hits on one of the most fiendish aspects of the legislation:

“One thing I would say about the legislation is it’s very clever; It’s clever, but it’s not good.

Hal Crawford, former Editor-in-chief and Publisher at ninemsn

The code is indeed extremely clever. During its development the ACCC took learnings from previous international attempts at getting digital platforms to pay news organisations and ensured that the mechanisms they put in place via the Code would make the alternative to paying so painful for the digital platforms that them paying news organisations was a fait accompli.

One such learning was when Spain tried to force Google to pay Spanish news organisations, instead of paying Google just shut down their Spanish news website. Google were no longer getting any benefit from having Spanish news on their platform, however with Google users in Spain still able to access French, British, and American news organisations it was no big loss to Google. It was a big loss to Spanish news organisations, particularly small ones which relied on Google to be discovered, and is still felt to this day.

To understand why the code is so clever in it’s attempt to avoid these types of situations, it’s important to understand some key definitions within the code. These definitions set up the devices within the code that interplay with each other and act as a binding grip on a digital platform, and its ability to avoid paying news organisations.

Core news content is a very narrow and limited term and can be summarised as anything that reports, investigates, or explains issues or events that are of public significance, or assist with public debate and democratic decision making.

For some publishers here in Australia, such as Michael West Media and Crikey this would cover the entirety of their content. For others like Nine Entertainment’s Sydney Morning Herald, Seven West Media’s The West Australian, and News Corp’s The Australian, not all their content would be covered by this term. For example, sports analysis or specialist technology coverage would likely not fit this definition.

Covered news content however expands dramatically on the definition of core news content, encompassing all that of core but further including any content that reports, investigates, or explains current issues or events of interest to Australians.

The large publishers mentioned in the previous section like The Sydney Morning Herald would likely have all the content they publish covered under this term.

A designated digital platform service (DDPS) is a digital platform designated as such by the Treasurer under the process defined in section 52E.

Importantly, these designations do not require any new law to be passed, and there is no dispute or consultation process prior to or after the designation being made. The Treasurer does have to consider “whether there is a bargaining power imbalance”, however there is no requirement for that to be the only consideration, or whether the outcome of that consideration actually be the determining factor of the designation.

So far, we have a situation on the Internet looking something like this:

Lastly, a registered news business (RNB) is an organisation which can obtain the benefits of the Code. The primary benefits one thinks of are financial benefits, however there are additional benefits that RNB’s will obtain under the code such as access to algorithm notifications, as well as information about data collected by a DDPS.

RNB’s have to pass a number of tests to be registered under the code, and importantly tests include that their primary purpose is to produce core news content, that their annual revenue must exceed $150,000, and that they are primarily based in Australia and serve Australian people.

Due to these tests, in the diagram above, news businesses that would be eligible to be RNB’s would be the publishers of Crikey, Michael West Media, The Australian, and The Sydney Morning Herald.

The Ultimatum

Where all these definitions work together to result in Facebook’s removal of news having to be so incredibly broad is in the Code’s section 52ZC, which houses its non-differentiation clauses. This is the part of the code created to place digital platforms in the binding grip I mentioned earlier, and it’s goal is to make it as painful as possible for a digital platform to attempt to reproduce what Google did with news content in Spain.

What this section states is that it is a breach of the code to differentiate between the covered news content of RNB’s and other covered news content, simply due to their registration as an RNB, or their eligibility to register under the code. Penalties for breaching this part of the Code can be penalties of up to 10% of annual revenue. The ways that differentiation is not allowed is in relation to crawling of, indexing of, linking to, showing an extract of, or reproduction of content – effectively every way that news content could be interacted with on a digital platform.

So when Facebook decided they were going to remove content of RNB’s from their platform, it wasn’t just as simple as Google’s action in Spain of removing just their content; they also had to remove all covered news content from their platform. This is put into plain words by Rod Sims, head of the ACCC in an interview with Politico in August 2020 where he described this non-differentiation:

“They can close the Google News service, but provided there is any news at all, domestic or international, shown on any Google service, such as search or YouTube [which Google owns], then they’re caught by the code and all the mechanisms,” he said.

Rod Sims, Chair of the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission

The key part in that quite showing the breadth of this non-differentiation clause is the “domestic or international” part. The tests to become a RNB make it clear that to be eligible for the benefits under the code you need to be primarily Australia-based, serving a primarily Australian audience. The fact that showing or linking to news of international content catches a digital platform in the code and it’s mechanisms is testament to the breadth of the code.

So in effect, the ACCC and the Australian Government through the Code provided an ultimatum to Facebook; They told Facebook that if they are to continue to show or link to covered news content on their platform they must provide all the financial and other benefits to RNB’s. Alternatively, they would need to stop showing and stop linking to any covered news content on their platform. They were confident the burden was too great for Facebook to wear. But Facebook, showing the audacity of a company which in a little over 10 years has grown to serve 2.8 billion active users, called their bluff and chose the latter option.

Shortly after the news ban came into effect, Twitter user Kevin Nguyen (@cog_ink) started a thread which documented the sweeping effect the ban had on the Facebook platform. Hundreds of pages of all kinds of organisations were now empty. The Australian Council of Trade Unions: gone. Queensland Health: gone. The Bureau of Meteorology: gone. RACQ: gone.

What’s important to remember is this excerpt from the definition of covered news content:

“covered news content means […] content that reports, investigates, or explains current issues or events of interest to Australians.”

Whether it be trade disputes, COVID-19, climate change, or a planned road upgrade in Queensland, it can be certainly argued that a number of those pages blocked “explain events of interest to Australians”. Facebook had to take down so many sites that are neither businesses nor what we would generally understand to be news due to the fact that these pages engage in the dissemination of what could be considered covered news content.

There are now reports that Josh Frydenberg and Facebook have spent their weekend negotiating changes to the Code. It seems now that the Morrison Government, small publishers affected by this news ban, and even the Bureau of Meteorology are unlikely to have a restful night for a while yet.